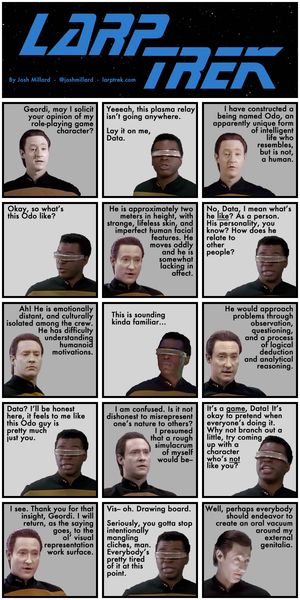

#017 - Big Book of Idioms + Thesaurus = Data joke generator

Data’s an impossible character who really only works in the sort of blindly optimistic and hand-wavey universe of Star Trek. I mean impossible in the sense that he just doesn’t really stand up to scrutiny because the needs of television writing and plotting won’t allow it. Which, to be fair, is true of just about everything in storytelling and in particular episodic, on-going TV shows, because the practical requirements of status quo force everybody’s hands in all kinds of ways. What makes the most exciting or interesting or challenging or shocking story in the short term doesn’t line up well with what makes for a sane production process over the long haul.

But Data shines a light on that more directly than most characters in Next Generation because he’s such a pure concept. Riker may be characterized by his ambition, his sense of adventure, and (though not to the degenerate degree I’ve been giggling my way through in this strip so far) his sensual/sexual drive, but there’s a whole lot of wiggle room even in those major character notes because he is after all a human being and full of complicated and contradictory urges. We can always plausibly discover secret feelings, held below the surface until a Very Special Episode. People have hidden depths.

But Data is by design not that sort of being; his robotic mind, his analytical nature, his explicit disconnect from and curiosity about the human condition (if curiosity is not too charged and subjective a description for whatever Data’s questing process is) is what defines him as a character, as a being alone in the universe. Not getting the humanity thing is his whole deal. His struggle to emulate basic emotions, to deconstruct and embrace even the superficial trappings of empathy, is what Data’s all about. If he has hidden depths, they’re as hidden from him as they are from everyone else, and he’ll tell you about the process of searching for those depths at the drop of a hat. No secret motivations, no undercurrent of selfish contradiction or fear or broken-heartedness: Data is deeply aware of the steady emotional wasteland that is his subjective experience of the world compared to organic humanoids, and is completely honest about it.

But he’s played by a human, and written by humans, and played against human(oid) characters, and ultimately he just doesn’t work in a Roddenberrian context if he’s not a more familiar reflection of humanity than his character sketch might suggest. The possibilities for the actual cold alien terror that is a fundamentally inhuman being in human form is fodder for lots of fantastic science fiction and horror storytelling, but it’s not really Star Trek then; certainly not a Star Trek protagonist. A truly dead-eyed, unfeeling ubermensch golem on the Enterprise? Not likely. (Consider for that matter that every close-up Star Trek examination of the Vulcans’ famously walled-off emotions is at least in part, and usually fairly centrally, an examination of the cracks in that wall and the turmoil lurking inside.)

And so we get to see Data not constantly, deeply unsettling everyone he meets but rather getting along with folks in a very successful way and only occasionally fumbling for acts I and II of a given episode; we see him struggling with language idioms in a way that makes for funny moments but doesn’t make a hell of a lot of sense coming from a walking Wikipedia with an otherwise tremendously powerful language engine (while of course casually sticking the landing on other idioms so entrenched in contemporary English usage that the writers didn’t think to make them seem odd in the 24th century). Data should probably be correcting everyone else’s language usage, if anything; a robo-pedant, the guy who learned your language more recently than you did but is better at it.

And we see him being affectless except for when (a) a scene is about him trying to explicitly model human affect and emotion as an experiment or (b) a scene where something just slips a little and we see Brent-Spiner-the-human-actor a little bit even though there’s not anything story-centric going on there with Data’s emotional state. And the latter thing is totally fine if subtle background character development is a part of your storytelling technique, but that’s not really the mode Next Generation operated in so it’s hard to read it that way.

But yes, so, Data is Data and not The Terminator. And he’s awesome and I love him even if Spiner gets caught in the occasional frame looking a little too much like he’s got, you know, feelings and stuff. But it’s a reminder that Star Trek is more morality play than character study most of the time, and comprises a delicate balancing act in audience suspension of disbelief if the viewer isn’t going to go a liiiiittle bit crazy about it all.

And it makes for a lot of easy subversions of that balance.

Anyway, Data as Odo felt more like it was a little funny being stretched to an on-the-nose comparison as a one-off joke than like it’d be particularly funny to play out in the strip long-term, so, hmm! Back to the visual representation oral vacuum it is.

tk

You can tell this is a comic strip and not a TV show because I didn't have to have Geordi actually keep fiddling with that plasma relay for most of the conversation just to keep something happening in the frame. On the down side, I also can't have him stop mid-conversation to set it down for effect.

This was one of the challenges of writing the strip that I hadn't anticipated when I started -- needing to elide props, stage directions, backgrounds, and (for the most part) any real cinematic vocabulary while keeping the impression of a familiar television show is a constraining thing! I mostly discovered things I couldn't do when I first started to try to write them into a strip; I'd have to rework dialogue or restructure a joke just to make it all work with brief chunks of text and a handful of canned facial expressions. It was often a lot of fun to try and solve those problems myself for the first time, but it was tricky too and I'm sure I had to trash at least a few ideas that were too visual to work.

I put a lot of thought into framing conversations on a 180 rule, though, speaking of cinemetographic language. Didn't always work and was always a bit abstract, but characters in an exchange on opposite framing felt important in order for things to read naturally.

And, more pathologically, I really wanted to avoid flipping images and having rank pips on the wrong side of a collar, so I ended up collecting both left- and right-facing shots for characters; one side of that was biased heavily in my Geordi collection because he was so often in conversation in the strip. But I cheated with certain characters who didn't have pips visible -- Wes, Keiko, Deanna -- and I'm pretty sure I cheated a few times by e.g. cropping close enough on a ranked character to hide the switch pips from view.